Jos de Mul, It takes three to tango. Over de tragische dimensie van Europa, in: Ronald Tinnevelt (red.), Europa. Op zoek naar een nieuw elan. Nijmegen: Valkhof Pers, 2014, 177-192.

“Het veroverde Griekenland veroverde haar onbeschaafde veroveraar en bracht de kunsten in het landelijke Latium.”

Horatio

Waar is Europa? Wanneer is Europa? Wat is Europa?

Wie vraagt naar de Europese cultuur wordt al snel geconfronteerd met enkele basale, maar lastig te beantwoorden vragen. Dat wordt al duidelijk als we de simpele vraag stellen waar Europa nu precies ligt. Dat hangt samen met het onderscheid tussen staat en natie. Spreken we over de EU, een bundeling van onafhankelijke en soevereine lidstaten, dan is er een precies, zij het nogal veranderlijk antwoord te geven. Bestond de EEG bij oprichting in 1958 uit 6 lidstaten, dat aantal is steeds verder gegroeid en sinds de toetreding van Roemenië en Bulgarije in 2007 bestaat wat nu de EU heet uit niet minder dan 27 lidstaten. En het is onwaarschijnlijk dat het daar bij zal blijven.

Het gaat me hier echter niet om de grenzen van de EU, maar naar die van de Europese cultuur. Die vragen hangen natuurlijk wel samen. In de discussie over de mogelijke toetreding van Turkije tot de EU gaat het immers ook, en niet in de laatste plaats, om de vraag of Turkije wel of niet tot de Europese cultuur behoort. Op die vraag is gezien het heterogene, open en daardoor veranderlijke karakter van de Europese cultuur geen enkelvoudig antwoord mogelijk. In de discussies over het Turkse lidmaatschap wordt vaak de nadruk gelegd op de verschillende religieuze tradities. Dat is inderdaad een belangrijk verschil. Maar daarbij mag niet vergeten worden dat het christendom en de islam allebei wortels in het jodendom bezitten, en dat de geschiedenis van Turkije nauw verbonden is met die van de huidige lidstaten van de EU. Als het om Europa gaat wordt – de Grieken voorop – graag verwezen naar de Griekse Oudheid als de bakermat van de Europese cultuur. Daarbij wordt vaak vergeten dat die Griekse cultuur voor een belangrijk deel tot ontwikkeling kwam aan de Ionische kunst van wat nu Turkije heet. Thales woonde in Milete en Herakleitos zag alles stromen (panta rhei) in Efese. En ook door het Rijk van Alexander de Grote, het Byzantijnse en het Otto- maanse Rijk (dat zich op haar hoogtepunt tot aan Wenen uitstrekte), is Turkije deel van de Europese geschiedenis.

De vraag wanneer Europa is, is al even lastig te beantwoorden. Is Europa een herinnering? Een realiteit uit het verleden, uit de tijd dat er nog Europese Rijken bestonden, zoals het Romeinse Rijk en de keizerrijken van Karel de Grote en Napoleon? Of ligt Europa juist in de toekomst, in het moment dat de economische, juridische, poli- tieke en culturele integratie van de EU is voltooid? Of is Europa misschien veeleer een utopie, een mythische gestalte, zoals de bevallige Europa uit de Griekse mythologie, de mooie prinses uit de stad Sidon (in het huidige Libanon), die door Zeus naar Kreta wordt ontvoerd om er de liefde mee te bedrijven, waaruit vervolgens de oudste cultuur van Europa, de Minoïsche, ontspringt? De oorsprong ligt immers altijd elders.

De vragen naar het waar en wanneer van Europa voeren onvermijdelijk naar een derde vraag: wat is nu eigenlijk het Europa waarnaar we op zoek zijn? In feite is dit de meest fundamentele vraag, aangezien we onze zoektocht naar de grenzen van Europa in ruimte en tijd pas kunnen aanvangen als we op zijn minst enige notie hebben van waar we nu eigenlijk naar op zoek zijn, of dat nu een verleden of toekomstige realiteit is, of een mythische gestalte.

In de poëzie van Gerrit Kouwenaar laten zich twee thema’s onderscheiden die, ofschoon ze op het eerste gezicht niet veel met elkaar te maken lijken te hebben, bij nadere beschouwing ten nauwste zijn verbonden. Het eerste, vaak genoemde thema betreft het autonome karakter van Kouwenaars poëzie: veel van zijn gedichten handelen over de taal en over het dichten zelf. Het tweede thema in Kouwenaars poëzie is minder opvallend, maar speelt daarin m.i. toch een bijzonder fundamentele rol. Het is - in Nietzsches woorden - het besef van ‘de dood van God’.

In de poëzie van Gerrit Kouwenaar laten zich twee thema’s onderscheiden die, ofschoon ze op het eerste gezicht niet veel met elkaar te maken lijken te hebben, bij nadere beschouwing ten nauwste zijn verbonden. Het eerste, vaak genoemde thema betreft het autonome karakter van Kouwenaars poëzie: veel van zijn gedichten handelen over de taal en over het dichten zelf. Het tweede thema in Kouwenaars poëzie is minder opvallend, maar speelt daarin m.i. toch een bijzonder fundamentele rol. Het is - in Nietzsches woorden - het besef van ‘de dood van God’.

One of the most striking developments in the history of the sciences over the past fifty years has been the gradual moving towards each other of biology and computer science and their increasing tendency to overlap. Two things may be held responsible for that. The first is the tempestuous development of molecular biology which followed the first adequate description, in 1953, of the structure of the double helix of the DNA, the carrier of hereditary information. Biologists therefore became increasingly interested in computer science, the science which focuses, among other things, on the question what information really is and how it is encoded and transferred. No less important was that it would have been impossible to sequence and decipher the human genome without the use of ever stronger computers. This resulted in a fundamental digitalization of biology. This phenomenon is particularly visible in molecular biology, where DNA-research increasingly moves from the analogical world of biology to the digital world of the computer.[1]

One of the most striking developments in the history of the sciences over the past fifty years has been the gradual moving towards each other of biology and computer science and their increasing tendency to overlap. Two things may be held responsible for that. The first is the tempestuous development of molecular biology which followed the first adequate description, in 1953, of the structure of the double helix of the DNA, the carrier of hereditary information. Biologists therefore became increasingly interested in computer science, the science which focuses, among other things, on the question what information really is and how it is encoded and transferred. No less important was that it would have been impossible to sequence and decipher the human genome without the use of ever stronger computers. This resulted in a fundamental digitalization of biology. This phenomenon is particularly visible in molecular biology, where DNA-research increasingly moves from the analogical world of biology to the digital world of the computer.[1]

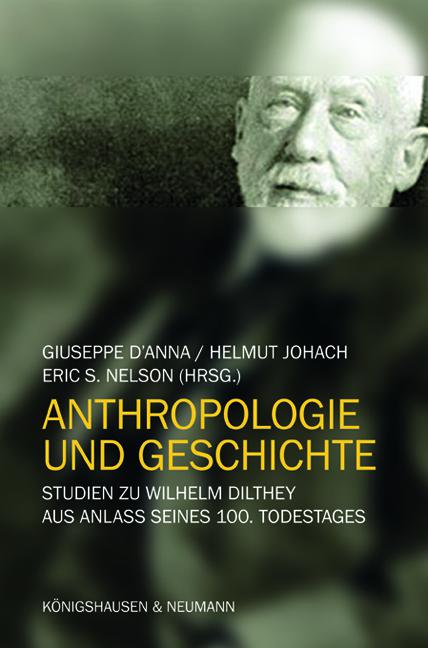

In Dilthey’s Lebensphilosopie, anthropology and history are closely connected. As Dilthey himself states in an often quoted remark: »Was der Mensch sei, sagt nur die Geschichte«.[1] However, for Dilthey history exclusively means cultural history. In order to develop a proper understanding of the historical condition of man, we should take natural history into account as well. After all, as a psycho-physical unity, Homo sapiens sapiens is the historical product of a complex interplay between both natural and cultural developments. Moreover, in the age of the life sciences, natural and cultural history seem to breach into one each other with an ever increasing tendency. Biotechnologies such as genetic modification, pathway engineering and genome transplantation transform organisms into cultural artifacts; and in the attempts to create artificial life (arguably the holy grail of synthetic biology), cultural artifacts increasingly display qualities that used to be restricted to organic life.

In Dilthey’s Lebensphilosopie, anthropology and history are closely connected. As Dilthey himself states in an often quoted remark: »Was der Mensch sei, sagt nur die Geschichte«.[1] However, for Dilthey history exclusively means cultural history. In order to develop a proper understanding of the historical condition of man, we should take natural history into account as well. After all, as a psycho-physical unity, Homo sapiens sapiens is the historical product of a complex interplay between both natural and cultural developments. Moreover, in the age of the life sciences, natural and cultural history seem to breach into one each other with an ever increasing tendency. Biotechnologies such as genetic modification, pathway engineering and genome transplantation transform organisms into cultural artifacts; and in the attempts to create artificial life (arguably the holy grail of synthetic biology), cultural artifacts increasingly display qualities that used to be restricted to organic life..png) The title of my talk today is “Redesigning (open) design” and the subtitle reads “Applying database ontology”. Let me start explaining this title, the question I want to address this afternoon and the answer I’m going to defend. One of the themes of Picnic 2010 is Redesigning design, of which (Un)limited Words and the (Un)limited Design Awards Ceremony are also part. In the program of Picnic 2010 the theme Redesigning Design is introduced as follows: “The design industry is going through fundamental changes. Open design, downloadable design and distributed design democratize the design industry, and imply that anyone can be a designer or a producer”. The subtext of this message seems to be that open design - for reasons of brevity I will use this term as an umbrella for the aforementioned developments, thus including downloadable design and distributed design – is something intrinsically good, so that we should promote it. Though my general attitude towards open design is a positive one, I think we should keep an open eye for the obstacles and pitfalls, in order to avoid that we will throw out the (designer) baby along with the bath water.

The title of my talk today is “Redesigning (open) design” and the subtitle reads “Applying database ontology”. Let me start explaining this title, the question I want to address this afternoon and the answer I’m going to defend. One of the themes of Picnic 2010 is Redesigning design, of which (Un)limited Words and the (Un)limited Design Awards Ceremony are also part. In the program of Picnic 2010 the theme Redesigning Design is introduced as follows: “The design industry is going through fundamental changes. Open design, downloadable design and distributed design democratize the design industry, and imply that anyone can be a designer or a producer”. The subtext of this message seems to be that open design - for reasons of brevity I will use this term as an umbrella for the aforementioned developments, thus including downloadable design and distributed design – is something intrinsically good, so that we should promote it. Though my general attitude towards open design is a positive one, I think we should keep an open eye for the obstacles and pitfalls, in order to avoid that we will throw out the (designer) baby along with the bath water.

.jpg) Volgens de Duitse filosoof Helmuth Plessner, die gedurende enkele decennia in Nederland heeft gewoond en gewerkt, is Nederland het enige land in Europa dat zonder romantiek is gebleven. Misschien is dat een tikkeltje overdreven, maar dat Nederlanders over het algemeen nogal vijandig staan tegenover de romantische beweging is evident. Toen het Van Gogh Museum dertien jaar geleden de tentoonstelling Philipp Otto Runge en Caspar David Friedrich: Het jaar en de dag organiseerde, waren nogal wat recensies ronduit negatief. Michaël Zeeman citeerde in zijn recensie de volgende passage uit de brief die Runge op 26 oktober 1798 naar zijn zuster zond: “Het kunstenaarschap is zoiets onbegrijpelijk moois, geen ander mens beleeft de wereld zo intens als ik en ik sta nog pas aan het begin. Wat een hemelse vreugde ligt er voor mij in het verschiet”. Volgens Zeeman is deze uitspraak een manifest voorbeeld van de stuitende zelfingenomenheid van deze schilder. “IJzingwekkende mededelingen zijn het”, zo schrijft Zeeman, “ook al verklaren zij veel. Samen met Runge's beeldende werk onthullen ze de gedachtewereld, of misschien moet je wel zeggen de gemoedsgesteldheid, waarin al dit verwarde getob op papier en die parmantige opschepperij in zwart-wit of full colour hun oorsprong vonden. Het is de wereld waarin onmatig veel heil wordt verwacht van de analogie-redenering, en waarin begrippen als 'inzicht' en 'wezen' overdreven vaak worden gebezigd, en dan ook nog op een tamelijk overspannen manier. Het is, kortom, de Duitse Romantiek in optima forma. En zelfs dat zou allemaal nog tot daar aan toe zijn, wanneer het resultaat maar niet bestond uit van die aanstellerige voorstellingen, die voor wat betreft Runge voornamelijk doen denken aan clichés uit negentiende-eeuwse drukkershandboeken” (Zeeman 1996).

Volgens de Duitse filosoof Helmuth Plessner, die gedurende enkele decennia in Nederland heeft gewoond en gewerkt, is Nederland het enige land in Europa dat zonder romantiek is gebleven. Misschien is dat een tikkeltje overdreven, maar dat Nederlanders over het algemeen nogal vijandig staan tegenover de romantische beweging is evident. Toen het Van Gogh Museum dertien jaar geleden de tentoonstelling Philipp Otto Runge en Caspar David Friedrich: Het jaar en de dag organiseerde, waren nogal wat recensies ronduit negatief. Michaël Zeeman citeerde in zijn recensie de volgende passage uit de brief die Runge op 26 oktober 1798 naar zijn zuster zond: “Het kunstenaarschap is zoiets onbegrijpelijk moois, geen ander mens beleeft de wereld zo intens als ik en ik sta nog pas aan het begin. Wat een hemelse vreugde ligt er voor mij in het verschiet”. Volgens Zeeman is deze uitspraak een manifest voorbeeld van de stuitende zelfingenomenheid van deze schilder. “IJzingwekkende mededelingen zijn het”, zo schrijft Zeeman, “ook al verklaren zij veel. Samen met Runge's beeldende werk onthullen ze de gedachtewereld, of misschien moet je wel zeggen de gemoedsgesteldheid, waarin al dit verwarde getob op papier en die parmantige opschepperij in zwart-wit of full colour hun oorsprong vonden. Het is de wereld waarin onmatig veel heil wordt verwacht van de analogie-redenering, en waarin begrippen als 'inzicht' en 'wezen' overdreven vaak worden gebezigd, en dan ook nog op een tamelijk overspannen manier. Het is, kortom, de Duitse Romantiek in optima forma. En zelfs dat zou allemaal nog tot daar aan toe zijn, wanneer het resultaat maar niet bestond uit van die aanstellerige voorstellingen, die voor wat betreft Runge voornamelijk doen denken aan clichés uit negentiende-eeuwse drukkershandboeken” (Zeeman 1996).